Properties of Some Randomized Minimax Game Trees

Zero-sum games are games where the sum of the payoffs of the players is zero. In other words, the gain of one player is the loss of the other. Examples of zero-sum games include chess, poker, and tic-tac-toe.

The zero-sum games that are turn-based can be represented as a tree. The root of the tree is the initial state of the game. Children of a node show the state of the game after a move. The leaves of the tree are the outcomes of the game. We can assign a value to each leaf node to represent the payoff of the game. The value of the leaf node is positive if the first player wins, and negative if the second player wins.

Also, for a zero-sum turn based 2 player game, the minimax algorithm can be used to find the optimal strategy for both players. Further detail can be found here.

The intuition behind the minimax algorithm is that both players wishes the worst for the other player to maximize their own gain. On odd depth, the first player tries to maximize the value of the node, and on even depth, the second player tries to minimize the value of the node.

Now assume that we know the probability distribution of the outcomes of the game. The question is, if the outcomes of a zero-sum game are equally likely, is the game “fair”?

Just mind that “proofs” in this post are not rigorous. It is mostly intuition based.

Simple example

Let’s start with a simple problem. Consider a complete binary tree of depth 2. Furthermore, set the value of the leaf node to be \(1, -1\). An example of such a tree is shown below.

0

/ \

0 0

/ \ / \

1 -1 1 -1

The last player to move in this game is the second player. The second player would choose min of the two possible moves. The updated tree would be

0

/ \

-1 -1

/ \ / \

1 -1 1 -1

Now, the first player tries to maximize the value of the node.

-1

/ \

-1 -1

/ \ / \

1 -1 1 -1

The value of the root node is -1. This is a winning game for the second player.

We see that if the leaf nodes are chosen, the outcome of the game is deterministic. Also, minimax algorithm starts from the leaf nodes. For formulation of problem, fixing the last player to move is a good choice.

Notations

Let’s now formalize the notations.

For simplicity, we say the min player always moves last. Furthermore, we say that the value of the leaf node is either \(1\) or \(-1\) with probability \(p_0\) and \(1 - p_0\) respectively.

We also denote probability \(p_i\) to be that the node is winning in hieght \(i\) to the player on that height.

Binary Randomized Game Tree

Let’s first write a truth table for a min player. The table is shown below.

| first node | second node | value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | -1 | -1 |

| -1 | 1 | -1 |

| -1 | -1 | -1 |

Now for the max player, the truth table is shown below.

| first node | second node | value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | -1 | 1 |

| -1 | 1 | 1 |

| -1 | -1 | -1 |

We see that the truth table is an or. A Node is winning for a player if it is not the case that both of its children are losing for the player. So equation can be written as

\[p_{i + 1} = 1 - p_i^2\]Furthermore, we also see

\[p_{i + 2} = 1 - (1 - p_i^2)^2\]Let’s focus on this equation as it captures the change in winning probability of one player.

Properties of the equation.

We first see that if \(p_{i + 2} = p_i\), then \(P_{i + 2k} = P_{i}\). The probability of winning stays constant. For compelte binary tree,

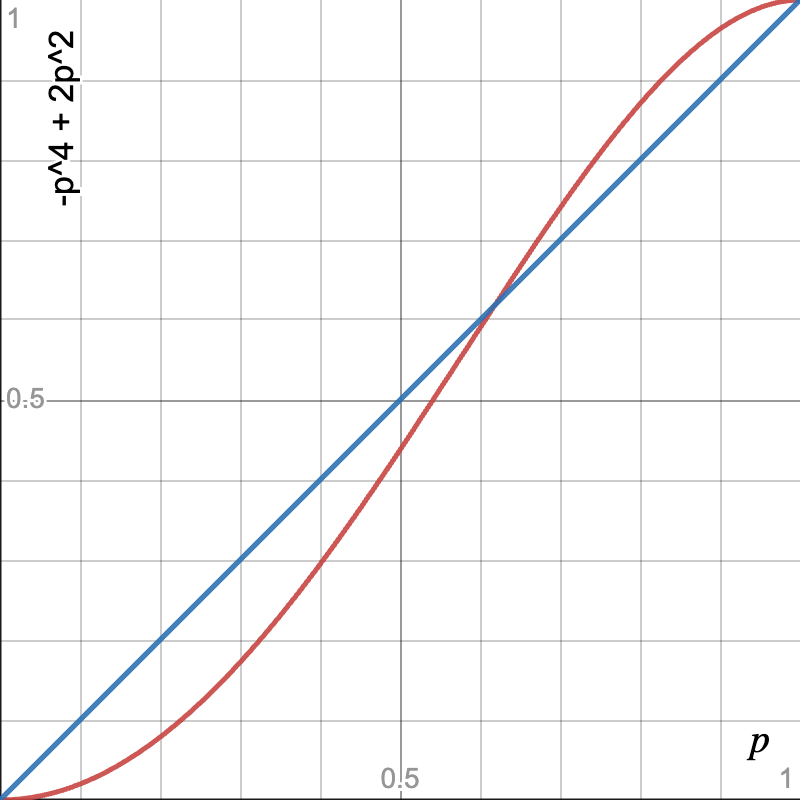

\[p = -p^4 + 2p^2\]So

\[p(p - 1)(p^2 + p - 1) = 0\]The roots are \(0, 1, \frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{5}}{2}\). The only point that is of interest is \(\frac{-1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}\).

Now, what if the starting probability is not \(\frac{-1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}\)? Let’s first draw a graph.

People who took dynamic systems would notice that if the starting probability is above the equilibrium point, the probability of winning goes to 1. If the starting probability is below the equilibrium point, the probability of winning goes to 0. The equilibrium point is divergent.

We can show the uniqueness of the fixed point by finding points of inflexion.

An interesting question is the speed of convergence.

Proposition

if \(p_0 < \frac{-1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}\), \(K \in \mathbb{N}\) such that for any \(n \in \mathbb{R}_+\), \(\frac{p_{k + 2}}{p_k} < \frac{1}{n}\) for all even \(k > K\).

Proof

\[\frac{p_{k + 2}}{p_k} = \frac{1 - (1 - p_k^2)^2}{p_k} = \frac{1 - 1 + 2p_k^2 - p_k^4}{p_k} = 2p_k - p_k^3\]We can show that \(2p_k - p_k^3\) goes to zero as $k$ increases. Thus the rate of convergence is larger than exponential.

Corollary

Let \(p_0 < \frac{-1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}\). Then there does not exist a $c \in R_+$ such that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(p_{2n} > \frac{1}{c}^n\).

Generalization to \($k-l\) tree.

Now, let’s generalize the result to a \(k-l\) tree. In this tree, each node in the same height have the same number of children, namely \(k\) for the min player and \(l\) for the max player.

We see that $p_{i + 2} = 1 - (1 - p_i^k)^l$. Using similar steps as before, we can show that there is a unique fixed point and the speed of convergence is larger than exponential.

Relation of \(k, l\) and the fixed point

Suppose we want to move the fixe point to the right. An intuitve way to do this would be to increase the number of \(l\), the choices for the max player. Conversely, if we want to move the fixed point to the left, we would increase the number of \(k\), the choices for the min player.

Is the increase in choices equally weighted? That is, if we set the number of choices for each player to be same, would the fixed point stay stable?

The answer is no. In fact, \(l \sim a \cdot n^k\)